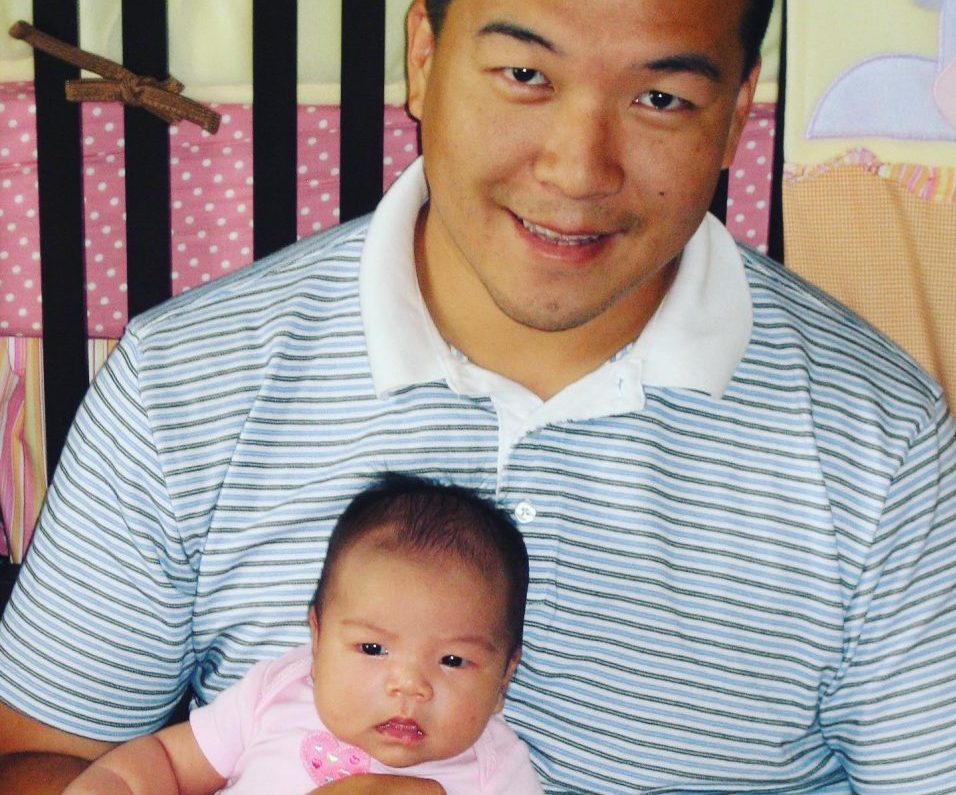

Most young kids will think of their parents as superheroes, but when Jimmy Choi’s daughter says so, it’s difficult not to agree with her. When we saw the man on the other end of the video call, in incredible shape with a kind smile and close cropped black hair, it certainly did bring to mind images of a slightly dyskinetic Superman

Jimmy credits his daughter’s unwavering belief that he really could do anything as a significant motivator for him to take part in the televised assault course competition, but his story starts a long time before then…

The beginning

In 2003 at the age of 27, Jimmy felt like he had his life pretty much together. He had graduated college with a degree in computer programming and was now working in tech during the .com boom. Entering into his third year of marriage with a great job, he had it all figured out. He began noticing “weird things” like twitches, rigidity and balance issues, but put them down side-effects of his demanding work life, or stiffness from his avid golf-playing. Although dismissive, he recalled advice from his father to purchase life insurance as soon as he started his own family, just in case. So that’s what he did, and it was at the mandatory physical exam that it first became clear something was up.

The exam went perfectly, until the drugs & alcohol section, where the nurse, on performing pupil dilation and field sobriety tests, began asking more and more questions. Knowing he had no problems and having just come up clean on his blood tests, became frustrated; “I don’t do any of that stuff, why are you asking me this?”. The nurse explained that she worked in a neurologist office, and recommended that Jimmy raise some of her observations, such as slow pupil dilation response and lack of arm swing, with his GP, although she never mentioned Parkinson’s. Again, Jimmy was dismissive, but ended up seeing a doctor nonetheless.

Hereafter followed 4 or 5 months of various appointments and referrals, culminating in one neurologist finally telling Jimmy, “I think you have Parkinson’s”. He didn’t know much about Parkinson’s at the time apart from that Michael J Fox and Muhammad Ali had it. Thinking it was an old person’s condition he felt confusion, anger and denial towards such a diagnosis at the age of 27. So he went to yet another doctor, who to his dismay agreed with the previous neurologist’s assessment and recommended taking L-DOPA and carbidopa. Still he fought it; why had none of the six or so doctors he had seen previously so much as mentioned Parkinson’s? He wanted a third opinion, and this time went to a movement disorder specialist. This time, the specialist took barely any time at all – he looked Jimmy up and down and straight away said, “You have Parkinson’s”. In spite of the mounting evidence, still Jimmy fought the diagnosis. He demanded further proof from DAT scans even though they would take months, and kept his diagnosis to himself, only telling his wife when he conceded that taking regular medication in the long term would be necessary, and that this would be impossible to hide from her.

The decline

At this point in the story, Jimmy takes a moment to (unnecessarily) apologise for taking so much time to describe the first 5 months of his experience with Parkinson’s. The good news, he says, is that it won’t take long for him to recount the next 8 years because he did “absolutely nothing”. Beyond taking his medication, which successfully staved off the worst of his symptoms, he spent no energy whatsoever attempting to manage his Parkinson’s. He never saw the movement disorder specialist other than get prescription refills, partly because his initial diagnosis was so blunt, brisk and impersonal. Knowing what he does now, Jimmy says he would have fired the guy on the spot for treating his patients with such indifference.

He threw himself into his work, thinking “I need to earn as much money as possible to support my family while I still can”, while at the same time isolating himself. Once, early on, he attended a Parkinson’s support group, but the experience only served to further distance him from his diagnosis. Walking into the room, he was presented with a group in which everyone was 50 years his senior, with whom he had nothing in common. He felt many of them had already given up. Their attitude towards him was negative too; they saw only his youth and rather than support him, they dismissed and minimized him. “You’re still young, you wait until you get this, or lose that”. They had nothing to offer Jimmy, and he had nothing to offer them, so he never went back. They alienated Jimmy not just from their social group but also from Parkinson’s itself – he felt invalidated, that at his age he could not really have the same condition as them, and it further fueled the resistance he felt towards his diagnosis

During these 8 years, Jimmy didn’t change his medication once. Jimmy likens his symptom progression to a child growing up. The transformation is so gradual that you don’t notice it as it happens, but suddenly you blink and everything has changed. After 8 years, his symptoms, once well-managed by medication, had caught up with him, partly because he made no effort to update his prescriptions. He exercised less and less, and ultimately became completely inactive. He began walking with a stick to prevent falls, and reached a weight of 250lbs. Seeing the man Jimmy is now, it’s almost impossible to imagine him in such a state. So how did he come back from this?

The ascent

Jimmy’s whole attitude towards life was changed in the course of a single event. He was at home and was about to carry his newborn son down the stairs. At the top of the stairs, he decided to leave his walking stick. Holding his son in one arm he thought he could rely on grabbing the stair-rail with his other to get down the stairs without falling. “This was probably the single worst, or in some ways the best decision of my life,” he says. He fell. Luckily, he managed to protect his son completely during the tumble and he himself was not seriously injured, but the episode took place in full view of his wife and daughter, and seriously shook the whole family. At this point he realised his negligence for his symptoms was putting his family at risk, and that at the age of only 35 he was becoming a burden for his wife. So he vowed to regain control of his symptoms. It was only then that Jimmy and his wife first opened the pamphlet he’d received the day he was diagnosed 8 years earlier.

At this point he didn’t know how he would tackle such a challenge. Despite having it for 8 years, Jimmy still didn’t really understand Parkinson’s or how to manage the symptoms, and so his number one priority became educating himself. Through his research he came to understand 2 things, he says; one, that he wasn’t smart enough to find a cure himself, and two, that he wasn’t rich enough to fund someone who would. So he concluded that the remaining option was to dedicate his body to science. He admits he was a little reckless, signing up for trials which carried the highest risk but the greatest possible reward – stem cell therapies, brain surgeries – with the mindset that if they went well that would be great and if something bad happened then that he was ready to accept it. During this intense period of testing, he noticed that many of the trials either included questions about or incorporated tasks involving physical activity. Moreover, he found that after completing such trials, with a forced movement component, his symptoms would improve and he would feel better.

This realisation marked the starting point of an incredible change within Jimmy, physically and mentally. Motivated by his discovery, he decided to make exercise part of his daily life. Bear in mind this was at a point where Jimmy was still severely overweight and required a stick to walk. So he started out small. The walk around his block was roughly a kilometre, so he began trying to circumnavigate it once a day. At first, he couldn’t do the full loop – he’d feel himself tiring and would have to turn back. But he kept at it, a little further everyday became his mantra, it didn’t matter how far he managed (or didn’t manage) to go as long as he tried and as long as he got a little bit further each time. With this resolve, little by little he built up his endurance and eventually completed the full lap, and eventually stopped using his stick to do so.

Between 2011 and 2012, this became Jimmy’s new drug. It improved his symptoms, his moods, his confidence is his own movement where previously he had been embarrassed or nervous to be seen walking. The improvement was so profound that one day Jimmy took another leap – he had regained his ability to walk, so why not try running? Again, it wasn’t easy at first and he had to build up his capabilities little by little, running just a little further every time. He felt rigidity when he started a run; breaking into a run was like trying to start up a stubborn motor and with every limb movement opposed by giant invisible elastic bands. Although looking relatively normal to an outside viewer, he would be focussing so hard on lifting his legs it would feel like he was trying to knee himself in the chest. On top of this there is always a chance that Jimmy will suddenly experience a shock of dystonia; “that son of a b*tch can come in at any moment and completely derail whatever I’m doing”. He describes the feeling as like a cramp that can last for hours. Sometimes dystonia can cause his toes to irreversibly curl underneath his feet, which of course can be seriously problematic mid-run.

Despite all this, once Jimmy gets going he describes feeling totally free and uninhibited. His self-consciousness subside even though his symptoms often remain obvious to observers. Perhaps, he speculates, as he achieves the famous “runner’s high”, his lack of dopamine is made up for by an increase in endorphins. However, even in this state he often eventually becomes hampered by his symptoms. He’s fallen many a time during his runs. However in these situations he tries to literally pick himself back up and tries to learn. What caused that fall? Is there a way I can avoid triggering this symptom? How can I get around whatever’s in my way and return to that feeling of freedom?

Running for more than just Jimmy

By this point Jimmy was feeling better and better and running further and further. He had started raising some money through his running, completing his first half-marathon in December of 2012. He remembers feeling so elated as he crossed the finish line that he immediately decided, then and there, to complete a full marathon by the end of the next month. To double one’s furthest distance run from 21km to 42km in one month would be a lofty goal for anyone, let alone for Jimmy who had been struggling to walk without a stick barely a year earlier. He knew this full well, and decided to use it as motivation to raise money. Still new to the running community he had no concept of how popular marathons were, and was astonished to find that all tickets for the upcoming Chicago marathon were sold out. He couldn’t so many people would actually pay to torture themselves by running 26.2 miles! Desperate to find a spot, he looked around online and found that the Michael J Fox foundation had reserved some charity bibs. By and incredible stroke of luck, they had just one remaining, which Jimmy eagerly took. However, it came with the prerequisite that he must raise $2000 for the foundation, which Jimmy now had less than a month to do.

Tho achieve the mammoth task, he turned to family and friends. For the first time since his diagnosis, he opened up about his Parkinson’s to people beyond those closest to him. Although apprehensive, it was important to Jimmy that he didn’t just suddenly announce his diagnosis and ask for money; instead he described his whole story and how much running had done for him and his management of Parkinson’s, much as he has kindly done here. Two things happened. First, contrary to his fears that people might pity or patronise him, he found that 99% of people are overwhelmingly, genuinely supportive of someone who is actively trying to better their situation. Second, in response to reading Jimmy’s story, many people, particularly other with young-onset Parkinson’s, started writing back to him, thanking him for sharing something they could closely relate and in some cases return the favour with stories of their own.

For the first time, Jimmy felt part of a Parkinson’s community that included like-minded people. They shared his passion for using exercise to treat parkinson’s and developed a rapport wherein people could exchange tips, tricks and workarounds. “If someone had a question about a particular movement,” he says “they would post a question and get three people answering it”. It was this mutual benefit, this collaborative attitude, that really solidified the community for Jimmy, and was miles and miles from that awful support group he’d attended 9 years earlier.

By the day of the race Jimmy had raised over $5000 for MJFF. He remembers standing on the start line thinking “I’ve just raised $5000 for charity, shared my story and started a community that has therapeutic benefit for me as well as all the other members, and I did it all in one month.” It was a profound realization of the opportunities he had squandered during the first 8 years of his diagnosis, and crystalised his resolve to continue to do better from thereon in.

Where we are now

Today Jimmy has completed 16 marathons, 105 halves, 1 ultramarathon, and countless other events. He’s even started his own race with his wife and together they have just under half a million dollars for Parkinson’s research. However he always says his greatest accomplishment was the community he created. This much was already clear to us; just talking to our own Charco participants and user testers about Jimmy, it’s clear how much energy he gives people who know about him.

As alluded to way back at the beginning of this article, the biggest boost to his community’s growth was thanks to his daughter watching American Ninja Warrior. She didn’t remember the 250lb Jimmy, she only knew him as the superhuman who can run 100km in a single day – to her he can do anything. So naturally, she suggested that he go on the show. Jimmy thought she was mad – he was just a runner. You need incredible upper body strength, grip and coordination to tackle the Ninja Warrior assault course. So he didn’t give it much thought at first. However, a couple years later he happened to another lady on the show with a disability that was probably equal in ninja warrior terms to Parkinson’s. If she could do it, what was stopping him – he decided he didn’t want to use his Parkinson’s as an excuse for himself or for his kids, and applied to the show on a whim. He was surprised when the show replied, very keen to have him on, and has been taking part every year since.

I highly recommend checking out some videos of Jimmy on American Ninja Warrior – they are amazing and beyond inspiring. Jimmy’s such a great character, and always has fantastic support from the crowd. In his first year, Michael J Fox himself even turned up to lend his support. Jimmy is extremely appreciative of the opportunity the show has given him to spread his story to a really wide audience. Since then he’s wanted to use his platform to help share how much exercise has helped him, spread awareness and raise funds for Parkinson’s, and 2 years ago, he left his CTO job to become a full time public speaker in the hopes of bringing more people together.

At this point I imagine some people reading this might be wondering if what Jimmy says and does can really apply to their own lives. It’s something Jimmy has encountered when giving talk around the country too – he often walks into the room full of people with Parkinson’s and, despite now being 45, still finds he is the youngest there. To help people relate, he does a simple exercise: let’s replicate it here. Put your hand up if you have Parkinson’s… Okay, keep your hand up if you were diagnosed more than a year ago, otherwise put it down… more than 2 years ago… more than 5 years… more than 10… more than 15…? At this point most people’s hands had returned to their laps, but Jimmy’s is still up. “I might be younger than you, but I’ve had Parkinson’s for nearly 18 years, so really I’m the senior here”. Having spent such a long time with it, I think it’s fair to say he knows a thing or two about Parkinson’s, don’t you?

Although he is a great champion of exercise as a Parkinson’s therapy, Jimmy’s well aware that running isn’t for everyone. “Running sucks, everyone knows that. It just sucks!” he jokes. Although it was what worked for him, he encourages people to find other things that might work for them. Particularly, he endorses identifying the activities or hobbies that people have let fall to the wayside because of their Parksinon’s, and finding alternative ways to do them and defying the limitations of having the condition.

Final thoughts

Jimmy is a pretty unbelievable guy, so it’s easy to forget, like his kids, that he hasn’t always been the superhero he is today. It took Jimmy nearly 9 years after his diagnosis to get to a point where he could do serious exercise similar to what he does now. He achieved his transformation through a great many small steps under the mantra of “a little further every day”, embodying the tortoise, not the hare.The bottom line, he says, is that movement is key – but it doesn’t have to be marathons. Start somewhere and break your long term goals into smaller, more attainable chunks: don’t try to do everything at once. This approach works for your symptoms too – try to work with your symptoms rather than against them, taking small steps to work around each one, rather than trying (and failing) to overcome them all at once.

This attitude, as well as a veracious desire to educate himself about Parkinson’s after his fall, were absolutely key, he says. Finding more information about Parkinson’s “is the best thing you can do (as long as it’s from a credible source)”. And if possible, learn with others. Jimmy had trouble finding his community, but once he did it became a very important part of his life. There are a lot of different people with Parkinson’s, and a lot of different communities out there, he says. Some won’t be right for you, but some will be; the trick is to find like-minded people. Thank you very much to Jimmy for talking with us! He has been an inspiration to so many, including us, we hope that this article will help spread his positivity and knowledge a little further.

Next on Jimmy’s list of goals is breaking a world record. This Saturday, 8th August at 4pm BST he will be attempting to break the current world record of 28 burpees completed in a minute. Follow his progress, watch his attempt live and donate to the fundraiser if you can over on his Facebook and Instagram. Best of luck Jimmy!

Author Alex Dallman-Porter

Stay up-to-date with our progress and be the first to know when CUE1 is available and on sale! We’ll also send you an introductory offer as well as further information on our research progress and testing recruitment.