Professor Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) is generally regarded as one of the greatest early neurologists; a pioneer whose diagnostic work has continued to influence medicine in the modern age. It’s hard to understate the influence Professor Charcot had on the field of neurology.

His work at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris attracted bright minds from across Europe, and many subsequent leading voices in Neurology, Psychology and Medical Science were his ex-pupils. Amongst his students were Sigmund Freud, father of psychoanalysis; Alfred Binet, inventor of IQ tests; Albert Londe, pioneer of X-ray machines; the American philosopher and psychologist William James, and Georges Gilles de la Tourette, from whom Tourette’s syndrome gets its name.

Charcot was instrumental in the classification of several different conditions, including Parkinson’s disease. His success was due to his belief in the importance of both clinical practice and laboratory work; in simultaneous treatment and research. He was, first and foremost, a keen observer (in fact, he considered ‘keen observation’ to be the highest compliment that could be given to a clinician). In treating his patients he would observe and measure their symptoms over time and compare his observations to the results of autopsies. This technique led him to effectively refine and further the descriptions of many different diseases, and in some cases identify lesions in the brain associated with them. He was certainly a dedicated practitioner – at least 15 separate conditions have been named after him.

Jean-Martin Charcot teaching, drawing by Paul Richer done around 1882. École des Beaux-Arts de Paris.

Jean-Martin Charcot teaching, drawing by Paul Richer done around 1882. École des Beaux-Arts de Paris.

Somewhat ironically, Charcot was the one who renamed ‘Shaking Palsy’ (or ‘paralysis agitans’) to ‘Parkinson’s disease’, after the original observations of English surgeon James Parkinson, despite Charcot directly challenging Parkinson’s original classification. As Parkinson wrote, this ‘shaking palsy’ was characterised by “involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power.. even when supported”. Charcot proved that tremors were not actually a necessary component of this condition, neither was muscular weakness. In fact, Charcot wrote that, until late-stages of the disease, people with Parkinson’s remained ‘remarkably strong’. Instead, it was ‘bradykinesia’ (slowness of movement) that prevented patients from performing a full range of action. His observations echo the writings of modern neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks; they both observe that Parkinson’s patients are capable of completing most motor tasks, if only at the price of being excruciatingly slow.

Charcot’s keen eye also helped differentiate Parkinson’s from other related conditions. He observed that Parkinsonian tremors were present at rest, isolating the condition from Multiple Sclerosis, and, by attaching feathers to his patients’ heads, he proved Parkinson’s distinct from ‘Senile Titubation’ by showing people with Parkinson’s do not nod! As well as Bradykinesia, Charcot also identified the component of ‘rigidity’ – now one of the main features of Parkinson’s diagnosis.

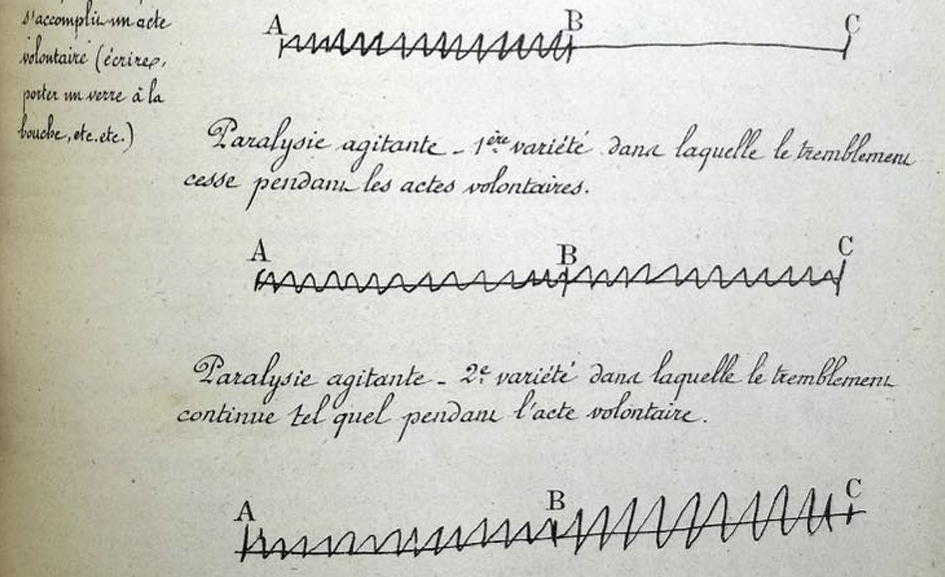

Schematic diagrams by Charcot of different shaking frequencies according to their etiology. Les leçons du mardi à la Salpêtrière, 1887 (page 417).

Schematic diagrams by Charcot of different shaking frequencies according to their etiology. Les leçons du mardi à la Salpêtrière, 1887 (page 417).

In reality, Parkinson was well aware his ideas were “in [a] state of immaturity and imperfection” and his original observations were a plea for the experts to take notice, and address this serious, over-looked disease.

In his fanciful words, “That these friends to humanity and medical science, who have already unveiled to us many of the morbid processes by which health and life is abridged, might be excited to extend their researches to this malady, was much desired; and it was hoped, that this might be procured by the publication of these remarks.”

Apt then, that Charcot would honour Parkinson for his first ‘call to arms’, incomplete as his characterisation may have been.

Himself a believer of innovation, Charcot consistently trialled the newest techniques of the time. He supplemented his own observations with other measurements of advanced empirical validity. To analyse gait, he had patients step in ink and walk on sheet-paper, to investigate Parkinsonian movement he employed the use of multi-frame photography. His written observations were frequently accompanied by the work of contemporary medical illustrators and sculptors.

He was pioneering in treatment too, implementing many novel methods of symptomatic relief. If they worked, he disseminated his results, if they were ineffective and/or disruptive to the patient, he dropped them.

He would tell students,

“If you do not have a proven treatment for certain illnesses, bid your time, do what you can, but do not harm your patients.”

For a man of his time he was comparatively forward-thinking. Charcot proved ineffective the practice of blood-letting and was one of first academics to suggest that ‘hysteria’ (which would now be diagnosed as an extreme anxiety- or depression-related condition) could be suffered by both women and men. His vision for incorporating breakthrough technology into his work was ambitious, and his openness to holistic ideas about health arguably helped kick-start the area of psychoanalysis, and the field of psychology as a discipline.

One of his areas of inquiry was the effect vibration had on Parkinson’s disease. It had been observed by Charcot and others that patients experienced an easing of symptoms after being jostled on a long carriage ride and that this effect persisted for some time afterwards. To mimic this movement, Charcot had a ‘Fauteuil Trepidant’ (vibrating chair) specially built. Powered by gas, steam or electricity, the chair would ‘oscillate’ in such a way to produce the same trembling as experienced while sitting in an open wagon or train carriage. The key to the professor was that the chair could be customised; the frequency, direction, and intensity of the vibrations could be changed depending on the patient.

Charcot was intimately aware of the individuality of Parkinson’s and other conditions. He considered the challenge of neurology to lie not just in the formation of an accurate and comprehensive ‘archetype’ of a disease, but in the flexible application of this to every individual patient, to appreciate their exceptions and idiosyncrasies:-

“Because the patient is so complex, he is a real study subject. After all, clinical medicine is above all the study of the difficult aspects and complexities of diseases. When a patient calls on you, he is under no obligation to have a simple disease just to please you.”

His chair was evidently considered a success. Patients were prescribed daily 30-minute sessions, and after five or six sessions their symptoms were supposedly diminished. While the vibratory therapy didn’t affect tremor, it reportedly eased stiffness and discomfort, and helped patients walk more easily, with ‘a feeling of lightness’. Remarkable also was the effect on the quality of sleep, with patients previously restless finding new somnial comfort. All this from a treatment, conversely, intolerably unpleasant for the neurotypical.

Their alleged findings are summarised in this particularly sensationalist extract from an 1892 issue of Scientific American:

“There could be nothing more insupportable for a well person than such shakes which demolish you, put you out of order, and shake up your intestines, and after a half minute’s experience, you would ask for mercy. The invalid on the contrary, lolls in the chair as you would on a soft sofa.

The more he is shaken the better he feels. After a sitting, he is another man. His limbs are relaxed, the fatigue has disappeared and the following night his sleep is perfect.”

Following these stories of success and somewhat lacking a proper anchor in the fundamentals of modern neuroscience, Charcot’s protégé went on to develop a rather silly-looking vibrating helmet. It was used to treat insomnia, migraines and melancholic depression and was thought to be more effective by virtue of directly shaking the brain (or ‘supplying vibration “delivered to the entire cerebral apparatus”).

Professor Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893).

Professor Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893).

After Charcot’s death research into vibration therapy almost entirely ceased.

‘Whole Body Vibration’ using devices similar to Charcot’s vibrating chair are currently sometimes used in orthopaedics, rheumatology and sports medicine. However, recent research into Whole Body Vibration to treat Parkinson’s and other motor conditions have been inconclusive. The improvements to symptoms that Charcot observed have been confirmed, but seem indistinguishable from the effects of other sensory stimulation – such as listening to music. Researchers who replicated Charcot’s chair in 2012 even suggested that improvements in symptoms could be due to participation in the clinical experiment itself, regardless of treatment. Perhaps the very fact that someone is treating you, paying attention to you is powerful enough to illicit symptomatic relief. It goes to show how researchers are constantly surprised by their results, especially in reference to conditions so complicated, only able to be truly understood holistically.

Nonetheless, thanks to Charcot’s work a link between vibratory feedback and Parkinsonian symptoms was solidified and has been the inspiration for research into modern vibratory techniques. The results of which now show that two specific interventions – focused stimulation’ and ‘pulsed cueing’ – can help relieve symptoms.

Charco Neurotech hopes to continue Charcot’s legacy of innovative treatment and his focus on patients as individuals and is proud to carry his name into the future of health-care.