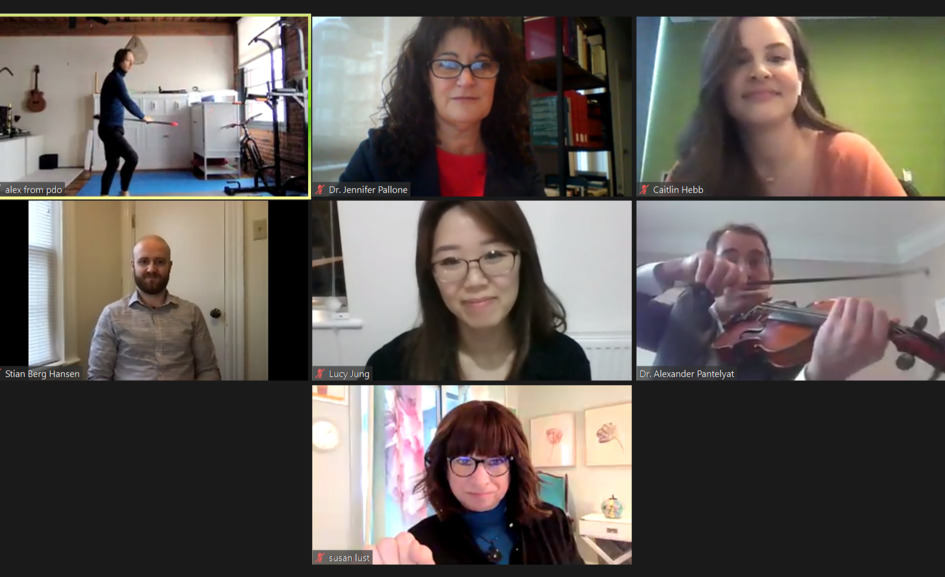

Charco recently gave a presentation at ‘Music as Medicine in Parkinson’s’, a seminar hosted by the Parkinson’s Wellness Project. This week, we share some of the insights we received from a panel of neurologists, performers, and therapists.

The Science

There are many ways in which music can help in managing Parkinson’s symptoms. Whether it be dancing to a beat, playing an instrument, or listening to your favourite song, music-based interventions can be extremely effective. The relationship between music, rhythm, and Parkinson’s is complex, and something which we are still in the process of fully understanding. By way of a brief introduction, Dr. Jennifer Pallone and Dr. Alexander Pantelyat lead the opening discussion, explaining the neurology behind these effects. To establish how music affects Parkinson’s, we must first understand the underlying processes which characterise Parkinson’s. As many with the condition will recognise, Parkinson’s impairs spontaneous movement. This can manifest itself in many different ways: often, people with Parkinson’s find it difficult to begin walking immediately after they have stood up. Conversely, people also struggle to stop walking once they have started.

Parkinson’s symptoms develop when there is a lack of dopamine in the body. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter, meaning that the nervous system uses it to send messages to other parts of the body. In people with Parkinson’s, this impairment of automatic movement is caused by the loss of dopamine-producing cells, which are located at the base of the brain. In pharmacological treatments, this loss may be, to some extent, “corrected”. With music, however, this is not the case. Rather, music offers people a way to, as Dr. Pantelyat puts it, ‘get around some of the issues with automaticity’.

Dr. Alexander Pantelyat

Dr. Alexander Pantelyat

One reason for this is due to an effect called “cueing”, by which the presence of repetitive, external stimuli help a person with Parkinson’s. Due to these stimuli, a person with Parkinson’s may carry out automatic movements, such as walking, with more ease. One example often used to explain cueing is a metronome. If a metronome, with its rhythmic, regular ticking, is placed in the same room as someone with Parkinson’s, they often find it easier to walk. Of course, for most people, the word ‘cue’ brings to mind an actor taking cues on how, what, and when to perform certain actions. This is a useful analogy for understanding Parkinson’s cueing. In essence, the external rhythm acts like a director, enabling a person with Parkinson’s to enact movements with a greater ease.

Nevertheless, this is only a part of the full picture. Music and rhythm can help with other symptoms of Parkinson’s too, and in different ways for different people. As Dr. Pantelyat explains, the full extent of this relationship is very hard to determine from a neurological perspective. Studies over the last several decades have shown that even just listening to music can activate as many parts of the brain simultaneously as any other human activity. Even more so, additional areas can be activated as a result of making music: that is, singing, moving to or making a beat, and playing a musical instrument.’

This poses a problem when attempting to study how music specifically affects the brain. As music affects many different areas of the brain, it is hard to find out how it specifically affects certain parts. ‘If things are getting activated simultaneously, it’s very difficult to design a study which just focuses on one region, and completely ignores what’s happening in response to music & rhythm in other parts of the brain.’

Whilst research may be ongoing, the benefits are abundantly clear. As Dr. Pallone notes, these benefits are not solely restricted to movement. The non-motor aspects of Parkinson’s are just as important, and are gaining more and more recognition as important parts of people’s treatment. People can ‘suffer from depression and anxiety, which has a really large impact on their quality of life’, and this must be taken into account for treatment to be effective.

Dr. Jennifer Pallone

Dr. Jennifer Pallone

Music-based interventions, as Dr. Pantelyat tells us, can be equally as effective in helping people manage these non-motor symptoms: ‘Having a music-based intervention that is combined with exercise, with rehabilitation […] can be very motivating for people to stay with.’

As his answer suggests, music has the edge over many other therapies for one key reason: it’s fun! Making something enjoyable is so often seen as a non-essential consideration, yet it can make the biggest impact. If people enjoy doing something, they are more likely to stay with it for longer, and do it more frequently. These types of therapy can also allow for more personalisation, as people are able to choose music according to their individual tastes. In these choices, there is no ‘one size fits all’, according to Dr. Pantelyat. Mozart ‘is not going to help everyone’; ‘the key is to find music and specific songs which really move you.’ This will be a welcome revelation to many. Metalheads and Ed Sheeran fans alike can come together, and share in the restorative powers of music and rhythm.

The activities done alongside music also play a vital role, as Dr Pantelyat stresses. ‘Think of music as a form of non-invasive brain stimulation, in this case auditory. There’s more to gain from doing it at the same time as you’re exercising, or making movements.’ In improving aspects of movement such as balance or walking, the key is to persist, and do activities repeatedly over a long duration. ‘This’, he affirms, ‘is crucial. If you don’t use it, you lose it. This goes for movement, this goes for all non-motor symptoms, this goes for the brain in general.’

Stian & His Guitar

Stian & His Guitar

Music Therapy

We know, then, that music can have a wide-ranging and impactful benefit for people with Parkinson’s. In the sections which follow, we learn more about how this can be put into practice.

To showcase one such method, we are joined by Caitlin Hebb and Stian Berg Hansen, two music therapists from MEDRhythms, a Neurologic Music Therapy company based across the USA. To begin, Caitlin explains the background behind music therapy: how it developed, and what it can achieve. The use of music for therapeutic purposes, in the form we know today, emerged around the early 20th Century. In the wake of two World Wars, music began to be recognised as an effective way to help veterans suffering from PTSD. However, as Caitlin explains, we didn’t begin to fully understand the effects of music until the 1990’s, when MFRA-imaging became available. ‘We could now really begin to see how music was impacting the brain, and musical functions such as speech and language. All of this research really helped the development of the field of neurologic music therapy, and in our development of standardised interventions applying music to areas like cognitive sensory and motor dysfunctions, which may have been caused due to a neurologic injury or disease.’

Caitlin and Stian now offer us a taster of some of the movement activities offered by MEDRhythms. For these activities, Stian provides the musical backing via his acoustic guitar, whilst Caitlin models the movement exercises. If you would like to try them out for yourself, please follow this video (starting at 30:00). For each exercise, Stian gives instructions, spoken in time with the rhythm set by his guitar. The pair show us three exercises, including weight shifting, forward-backward stepping, and finally some walking. Though these exercises may seem relatively uncomplicated, the potential benefits are massive. Combining movement and rhythm is a great way for people with Parkinson’s to maintain their motor abilities, and the knock-on implications in daily life can be truly transformative.

Caitlin Demonstrates Breathing Exercises

Caitlin Demonstrates Breathing Exercises

We now move onto singing exercises, led by Caitlin. Parkinson’s can diminish the strength and pitch of an individual’s voice over time, leading to quiet and strained speech. Singing can be the perfect way to manage these effects. As Caitlin explains, ‘speech and singing use the same muscles for respiration and articulation’, and share many of the same brain processes. Both exercises ‘contain elements of rhythm, pitch, dynamics, tempo, and diction’, and so exercising one can improve the other. Again, to try these activities for yourself, simply follow this video starting from 37:00. Caitlin employs a combination of breathing, speaking, and singing exercises, guiding us into using different pitches and tones. In each, you can feel your voice straining just a little bit more; for those of us who aren’t singers, it may serve as a reminder of how little we test our vocal range day-to-day!

The beauty of using something as diverse as music is that it can be tailored to anyone’s preference, as Stian and Caitlin’s activities serve to demonstrate. As both their movement and singing exercises show, music can serve many functions as therapeutic intervention. It can be a backing, an expression, a goal, or an instruction; indeed, it can be all of these at once.

A Music & Dance Duet Conversation

For the next section, Dr Pantelyat returns, albeit in a new capacity. During this section he will be playing the violin, accompanying Alex Tressor, a renowned broadway dancer and ballet instructor. Alex was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2007, at the age of 47. In his earlier life, he had achieved turning his passion into his career. In the years post-diagnosis, dance has assumed a new role in his life. It is now, as Alex himself explains, also a necessity in maintaining his quality of life, using it as he does to keep his symptoms at bay. Alex understands the importance of movement, and has dedicated himself to helping others experience these benefits. He regularly leads dance classes for people with Parkinson’s, in an effort to teach others the value of his own hard-won lessons. His message is simple; ‘If you don’t know how to dance or exercise, just try, because the alternative is pretty grim. We either move, or we don’t. We have to be our own advocate.’

For the session today, Alex shows us three dance exercises, each with their own unique style and metre. You can find the performance in full here, beginning at 50:00. Alex begins with a march, followed by a tango, and ending with a waltz. Alex is quick to note, however, that these are only examples, to offer people a brief snapshot: in your own exercise, any style of dance can be beneficial. When choosing your own dance and accompaniment, individual taste must be paramount. You should, he tells us, ‘pick something which you’re familiar with. You have to work out because you love it; you have to ride a bicycle because you love it; and you have to dance and listen to the music which you love.’ Become inspired, he advises, and allow the movements to follow.

In convincing people of dance’s benefits, Alex often finds that people dismiss it as “not for them”. Dance is frequently seen as inaccessible, as it can be associated with rigorous training and discipline. Nonetheless, Alex stresses, in its essential form ‘dance is a motor function like anything else. It’s like moving with frequent stops. You may become more elaborate, you become more eloquent in your movement: but really, it’s just seeing what the music tells you, and showing it in your body.’

Alex with his Schnauzer

Alex with his Schnauzer

Following from this discussion, Alex performs three short dances, each in a different style. Accompanied by Dr. Pantelyat on violin, he first showcases a march. Making short, staccato movements, the beat is heavy, with each new step decisively marking the rhythm. Next, we have the tango. Traditionally evoking passion, tango is a partner dance. Of course, with the pandemic as it is, dance partners are in short supply. Alex improvises his own solution, swiftly producing a broom as his makeshift companion. Impressively, this does little to lessen the dance’s impact. Alex still manages to give a fiery performance, despite the wooden execution of his partner. We now move to the final dance of the session, the waltz. For this dance, Alex takes a new partner: his daughter. Despite being a toddler, she manages not only to upstage the broom, but even manages to outshine Alex himself.

Thank You!

Thank you to the Parkinson’s Wellness Project, and to all the contributors who made today’s article possible. In the space of one short seminar, we received some brilliant examples and discussions on the roles which music and rhythm play in Parkinson’s interventions. We hope that these overviews will have sparked new interests for you, and given you new pathways to explore. If you would like to learn more about the Parkinson’s Wellness Project, please visit their website or contact [email protected].

Thank you for reading! Hope to see you again very soon :)