Parkinson’s disease is named after the first person to recognise it as a distinct illness – Dr. James Parkinson (1755-1824). An interesting figure, he was not just a good doctor but a keen scientist, political reformer and philanthropist.

Safe to say his life was fruitful and interesting. This article seeks to detail his achievements, hopefully showing a man who is fit to emulate. A man who cared for every person, regardless of background, as he believed individuals’ physical, moral and intellectual health amounted to the progression of society as a whole.

A Village Doctor

Hoxton, 1827.

Hoxton, 1827.

April 11th – World Parkinson’s day, and also the day James was born in 1755. James was the son of a surgeon, and followed his Father into medicine, apprenticed under him for 7 years, and eventually took over the running of their practice ‘Parkinson and Son’ in their home town, Hoxton. He received a thorough education, and was from a solidly medical family; the practice was subsequently passed down through four generations, and saw London and its residents change dramatically through the years. James lived through the advent of the industrial revolution. His patients in Hoxton changed from upper-middle class to working class, as droves of labourers populated the new factories of London and the city swelled and engulfed the surrounding suburbs.

Many of the old inhabitants of Hoxton moved away, but James didn’t. In Hoxton square he took to treating the evolved community around him and accrued a lifetime of diligent doctoring and remarkable medical achievement. He was a prolific writer – his books and pamphlets were not insignificant to medical academia of the time. We can thank him for perhaps the first proper descriptions of appendicitis and gout in British literature, as well as for developing techniques for the resuscitation of people recently drowned or hanged. All this alongside his main practice! It’s worth noting that James wasn’t a highly educated academian, or a leading surgeon in one of London’s main hospitals – in fact, after what little hospital training he did undergo he still remained, in his own words, ‘miserably ignorant’. No, James seems to have been a committed but strictly local Doctor, engaged in medical literature and making contributions where he deemed his findings worthy of publication.

The power of Observation

This, alongside the poor understanding of neurology at the time, makes his identification of ‘Shaking Palsy’ (now named ‘Parkinson’s disease’ in his honour) all the more remarkable. From observing his patients and neighbours for many years he decided to write a classification of what he understood to be distinct, but little-talked of condition. Almost 300 years on, his descriptions are still broadly accurate. He identified Parkinson’s as involving a tremor and a disrupted motor performance, affecting posture and balance, but having no necessary effect on the ‘senses and intellects’.* Doubtless through attention to his patients’ complaints, he notes how the disease affects everyday life; how people with Parkinson’s at first may notice problems with ‘fine motor skills’ (especially affecting eating and writing), how their sleep and bowel movements may become distressingly disrupted, and how, in later stages, navigating out of the way of a small obstacle when walking becomes a definite challenge and source of anxiety.

More markedly, Parkinson identified key components of the disease which form its key characterisation today. Firstly, that it is a progressive condition, starting as a barely-noticed hindrance and progressing into serious disability:-

“So slight and nearly imperceptible are the first inroads of this malady, and so extremely slow is its progress, that it rarely happens, that the patient can form any recollection of the precise period of its commencement.”

Secondly, that while Parkinson’s is a motor-disorder (and Parkinson named it a ‘palsy’ – paralysis, accordingly), the cause is not a weakening of the muscles themselves, but in a disorganisation/deficiency in what controls them.

“By the nature of the symptoms we are taught, that the disease depends on some irregularity in the direction of the nervous influence; by the wide range of parts which are affected, that the injury is rather in the source of this influence than merely in the nerves of the parts.”

Parkinson was also quick to point out the condition didn’t seem to have any identifiable, external cause (despite some of his case studies assigning their disorder to sleeping on cold ground or overindulgence of ‘spirituous liquors’). In a time of puritan Christianity it would have been easy to assign the disease to vice or moral decay, but Parkinson remarks that some of the afflicted have led lives ‘of remarked temperance and sobriety’.

* Although we now understand that progression of Parkinson’s does affect the senses; patients can suffer from loss of sense of smell and disruption of proprioception – the ‘sixth sense’ of body-position and self-movement theorised in the 1800s. Parkinson’s disease is also accompanied with a much greater chance of developing dementia and experiencing brain fog.

Medicine of the Time

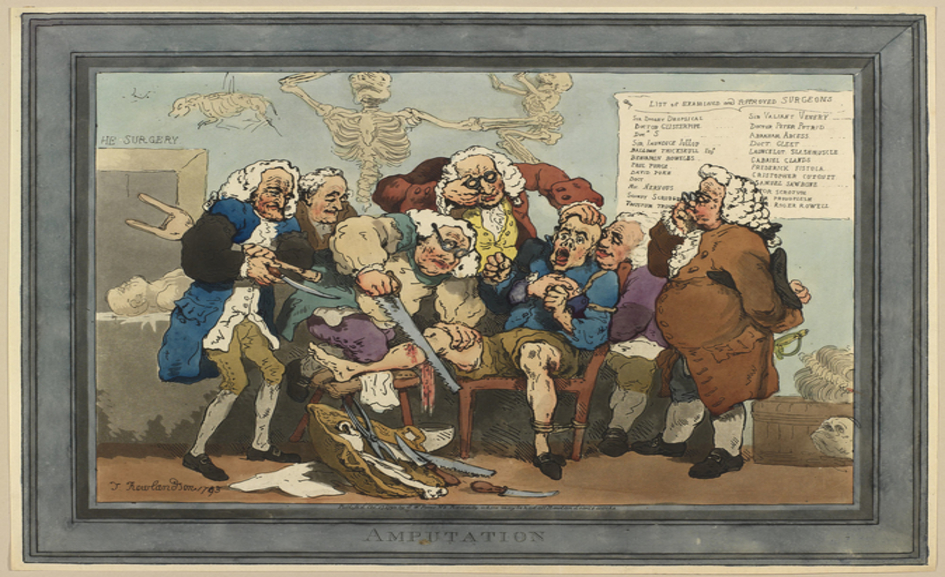

Parkinson implicated the spinal cord as the main culprit in this disease. Although he wasn’t exactly sure what structure in the spinal cord was to blame, he was sure the disease could be treated by – and Dr. Parkinson was quite optimistic about this soon becoming a definitive cure – by letting blood from the top of the neck. Now, this obviously doesn’t work (if only it were so simple!) but let us give James the proper context. At the time he wrote this paper medical science was in its relative infancy. Understanding of the body still relied on Ancient Greek principles; there were four substances that defined your health (blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm) and each of these was associated with a certain organ, personality trait and season. Diseases were said to be caused by a dis-balance of these basic elements, or an accumulation of poisons, and so a great many treatments in the 17th century involved dispelling liquids (particularly blood) from the body. In the year Parkinson published his book, Darwin was only eight years old. This was before germ theory, before the widespread use of anaesthetics, way before the modern notion of ‘hygienic’ surgery. Amputations were the most common surgery, and most people didn’t survive. In fact, to live to adulthood was statistically rare – three quarters of children never lived past the age of five.

Depiction of an Amputation, T Rowlandson, 1783.

Depiction of an Amputation, T Rowlandson, 1783.

Given all this, the extent to which his paper still holds up today is incredible. Parkinson only wrote the book (his only contribution to the field of neurology!) hoping others more qualified than himself could investigate further, but it was a long time before his work ceased to be the most accurate thesis on the subject. This was an era where any well-educated man, if he paid attention enough, could potentially make contributions to more than one burgeoning science.

A fossil apostle

James Parkinson was no exception. His intellectual interests extended way beyond medical science – by far his expertise was palaeontology, the study of fossils, on which he was said to impart information freely and enthusiastically. He was an avid collector of fossils and his collection was so impressive that he set up a museum in his own house, titled “The Cabinet of Coins and Medals” which was reputably quite popular. ‘Medals’ here is used in the sense ‘Medals of Creation’; Parkinson, like most people of the time, was a religious man and viewed palaeontology through a Christian lens, believing that these petrified remains were from antediluvian creatures – animals killed off by the biblical flood.

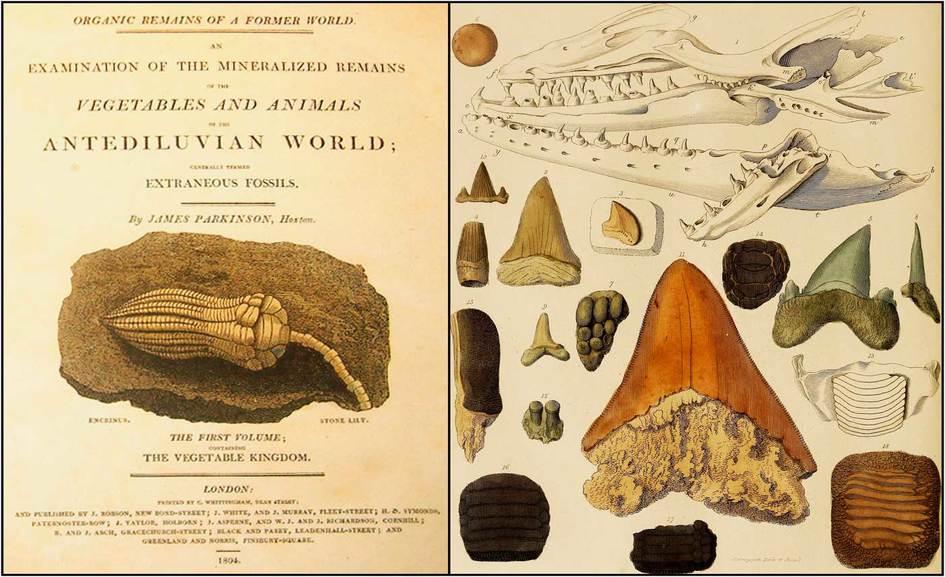

Front Piece of Parkinson’s work on Palaeontology.

Front Piece of Parkinson’s work on Palaeontology.

Nevertheless, his findings required some liberal interpretation of the Bible. Parkinson reconciled his religion and the hard evidence by interpreting the ‘seven days’ of creation as allegoric rather than literal, each ‘day’, he chose to believe, actually referred to a period of thousands of years. In 1804 he published “Organic Remains of a Former World”, a comprehensive overview of his specimens with illustrated diagrams, which became the standard textbook for Palaeontology in Britain. It was the first full attempt to detail fossils and offer scientific explanation, which is why Parkinson can be considered a ‘grandfather’ of this field. Many fossils have been named after him, and a few years later he solidified his legacy by co-founding the Geological Society of London; which still operates to this day.

Rocking the boat

If that wasn’t impressive enough, Parkinson was also a staunch political reformer and critic of the then powers that be. At the end of the 18th century he penned a good few outspoken pamphlets under the name ‘Old Hubert’. The French Revolution was happening in France; the British establishment was rightly wary and cracked down hard on any potential opposition. Outright criticism of the government or royalty wasn’t just potentially dangerous, it was outright illegal. In 1792 a Royal Proclamation made prosecutable any publication of ‘wicked and seditious writings’. Parkinson, however, didn’t hold back even in his first political publication:-

“Among the enemies of the human race, foremost appear the petty PRINCES OF GERMANY [the King and his son], who enact the ravages of despotism on a smaller, and consequently more oppressive scale; who plunder the peasant to maintain absurdly disproportionate establishments; who drag him from his home, the son from his parents, the husband from his family, to form under the rigour of military discipline the instruments of new exaction; who fell the blood of their subjects to swell the pride of a master, and have the insolence to call this GOVERNMENT.”

– The Budget of the People, ‘Old Hubert’.

Parkinson wrote in defence of the demographic of his practice: the ordinary poor. Politically, he was concerned with achieving fair representation in the House of Commons, and getting everyone the right to vote. Also a critic of government incompetence, he rallied for better education, a better justice system, better care for the infirm and an end to suffocatingly high taxes and the cycles of poverty. He was, through-and-through, a radical. His writings – which were written by candlelight in the early hours of the morning despite a busy day in practice before and another looming with the dawnlight – made ‘Old Hubert’ very popular amongst the masses, but decidedly unpopular among government officials.

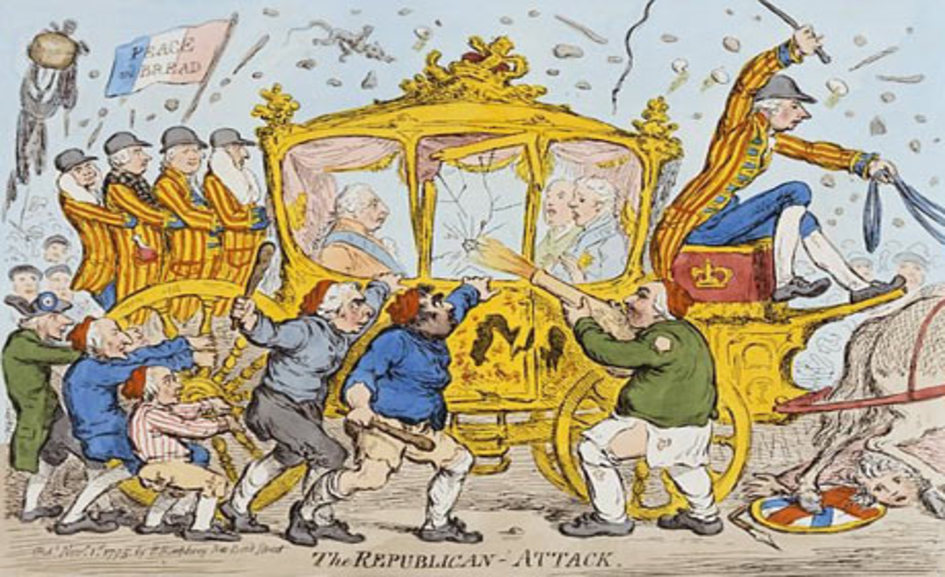

Scene of the King’s carriage being attacked by a mob, where he was allegedly shot at by a dart-gun.

Scene of the King’s carriage being attacked by a mob, where he was allegedly shot at by a dart-gun.

In the end, Parkinson’s work came back to bite him, as he became associated with a bizarre plan to kill the King with a poisoned blow-dart, the so-called ‘Pop-Gun Plot’. A high charge indeed – in those days it was literally high treason to even think about killing the King. As it turned out, this assassination attempt was almost entirely fabricated by officials looking to get rid of troublesome protestors – Dr. Parkinson’s peers in the London Corresponding Society. Revealing himself as ‘Old Hubert’ and risking harsh government reprisal, he bravely appeared as a witness to defend his colleagues. He, apparently, won over the Privy council with his ‘frankness, sincerity and integrity’, and the British jury system prevailed; the men were acquitted due to lack of proper evidence. These events must have properly spooked him however, as after this he seemed to withdraw from such active politics and devote his attention to community medicine and his academic pursuits.

Parkinson the philanthropist

That is not to say he turned his back on his ideals. In the spirit of overachievement Parkinson continued to contribute to society above and beyond his profession as a surgeon. He worked part-time in a psychiatric asylum (then called a ‘mad-house’) and campaigned for the reform and improvement of such institutions. He also helped mitigate an outbreak of typhoid fever in Hoxton by ensuring separate fever wards were assembled, stopping the spread of the disease.

He was well-known among the people for publishing medical booklets designed for the average citizen. He wasn’t just a practitioner of surgery, but concerned with the holistic welfare of the population. He wrote on many everyday issues, concerning common ailments and household cures; how best to rest and recuperate; and how to raise children. One stranger publication was ‘Dangerous Sports’, a gruesome, injury-laden story-book for children, aimed at “warning them against wanton, careless, or mischievous exposure to Situations, from which alarming injuries so often proceed.”

These medical works were well-read and went through several editions. Upon his retirement, Dr. Parkinson published a huge handbook to promote public knowledge of health, ‘The Town and Country Friend and Physician’. Besides specific diseases, it covers a great many topics; exercise, diet, the importance of intellectual pursuits, rest and amusement, the restorative power of nature, importance of talking to and raising your children, even if you consider yourself ‘uneducated’. From this book it was obvious James was pragmatically puritan; conscientious and empathetic towards his audience. He refers to love of alcohol as an ‘insidious enemy’, but admits that even he is “well acquainted with the delightful refreshment a glass of ale or spirits yields”. For the most part, he speaks straight-forwardly about the need for moderation and balance in life – and that what works for one person, might not work for another.

He warns, “You may if you choose make an amusement of labour; but never make a toil of amusement.”

and quotes Shakespeare:-

“[It is sometimes right] to frame your mind in mirth and merriment, Which bars a thousand harms, and lengthens life.”

For Parkinson, healthcare was obviously about more than just ensuring physical intactness and removing serious pain. Healthcare was about encouraging a fully realised life, a life that could be enjoyed and put to good use. He certainly used his well, selflessly committed to the care of others for nearly thirty years; an extreme devotion to medical practice and philanthropy – a career detrimental to his own wallet:-

“a physician seldom obtains bread by his profession until he has no teeth left to eat it.”

“I find myself, at the end of my labours, a poorer man than when I commenced them.”

James might not have been rewarded fiscally for his efforts, but he will be remembered.

A Man of Mystery

But how best to remember a man who died before the invention of photography? James Parkinson may have been a prolific writer, a champion for the rights of the working class, a defender of free speech, and an important contributor to more than one science but he left this planet without leaving much clue as to what he looked like. I would like to offer my thanks to some image of him, to visualise the great man.

I can only offer this:-

In 1789 James Parkinson, apparently, was the serving surgeon at the Oddfellow’s Grand Imperial Lodge in Old Street Square, London. The Oddfellows is a very old tradesman’s guild and, luckily for us, on one night in 1789 they commissioned a satirical engraving of their meeting. Perhaps the Oddfellow here holding a medicine bottle is who we should offer our gratitude to…

Source: London Metropolitan Archives

Source: London Metropolitan Archives